Discussions about Eric Harris often drift into speculation, and his parents are no exception. Over the years, they’ve been condemned on the basis of assumptions rather than evidence, particularly the idea that they didn’t love their son or discarded him after his death. This post is an attempt to cut through that noise by laying out a clear timeline. What we know about Eric’s parents’ actions and responses, and what I believe most likely happened to his ashes. To understand either, we need to start from the beginning.

April 20th 1999

Eric Harris committed his crime on April 20, 1999, when he and Dylan Klebold carried out a mass shooting and bombing at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. Eric Harris died by suicide on the same day, April 20, 1999, inside the school library.

What followed is often treated as an afterthought or worse, reduced to assumptions about what his parents must have felt or done. Wayne and Kathy Harris were left to navigate the immediate aftermath in near total isolation, under intense public scrutiny, and with very limited ability to speak for themselves. From this point on, I want to focus on what we can factually establish about their actions and circumstances after April 20, alongside my own interpretations.

Wayne and Kathy

Circa 1999

The first firsthand account we have of Wayne and Kathy Harris comes from the immediate aftermath of the shooting, through Ellis Armistead, the private investigator hired to protect and manage them during those first chaotic weeks. This is often where people stop reading because one line, spoken in shock, is repeatedly isolated and treated as definitive proof of how Wayne Harris felt about his son.

Armistead describes the scene like this:

“ His staff members drove Katherine and Wayne Harris to the Warwick Hotel in downtown Denver, checked them in under Armistead’s name, and waited for him to arrive. When he walked into the room, Katherine Harris was curled into a fetal position and sobbing. Wayne Harris came up to the investigator and said, “Just flush him!” Armistead’s job was to keep the couple secure for the next few weeks, as they moved into and out of a series of hotels. During that time, he watched as “some of the nicest people I’ve ever met” tried to accept the horror of what their son had done. “The father and mother,” he says, “were collateral damage in Eric’s crime. I don’t think people understand what that really means and how many others are affected by major crimes: families, victims, first responders, judges, juries, law enforcement, witnesses, lawyers and private investigators. After things began to settle down, the parents went back and lived in their home. The neighbors made a point of running off the press so they’d be left alone. I thought that was commendable.”

That single sentence, “Just flush him”, is often treated as a final verdict on Wayne Harris as a father. But pulled out of context, it loses the circumstances in which it was spoken. Early hours into confronting the reality that his son had committed mass murder and was dead, while his wife was physically collapsed in grief. I’ve said before, and I still believe, that this was an expression of overwhelming shock, horror, and self directed rage, not a measured statement of how Wayne felt about Eric as a person. People place far too much weight on that line, while ignoring everything else Armistead observed about the parents and everything else that is out there.

Not long after that initial, raw moment in the hotel room, Wayne and Kathy Harris participated in a formal meeting with investigators. This is one of the clearest windows we have into how they spoke about Eric when given time, structure, and the chance to reflect, rather than reacting in shock. What stands out in this account is not denial or detachment, but grief layered with disbelief, confusion, and an effort to make sense of who their son was versus what he had done.

This is an excerpt from Jeff Kass’ book describing the meeting:

“(…) the Harrises gave a history of Eric’s life up until Columbine, Dave Thomas says. His account begins to fill in some of the details the sheriff’s office will not discuss.

The approximately two-hour meeting took place at the law offices of Harris attorneys (…) “They [the Harrises] basically narrated for a couple of hours.”

“Wayne and Katherine Harris (brother Kevin Harris was not there) came across as “a pretty normal, suburban family who obviously cared about their son, cared about their family, thought they did things the right way,” said Thomas. He thought they were more cautious than the Klebolds. Wayne looked to be controlling his emotions, possibly owing to his military background. Nothing struck Thomas as inappropriate in the way the Harrises acted.(…)The Harrises, apparently, had thought through the presentation of Eric’s life they would give, but it did not seem canned, according to Thomas. Katherine Harris talked more than her husband.

“They had a lot of photos with them,” Thomas said. “They passed them around and let us look at them and I think at least the sense that I got is that they were very passionate about wanting us to understand that this was a young man not unlike most young men. That he wasn’t some diabolical monster, or that he had been causing trouble throughout his life and was somehow a bad seed, so to speak. That’s the impression I got. Lots of family photos, and birthday parties, and soccer pictures, and places they’d lived, photographs of places they’d lived.

(…) Investigators asked small-time questions, such as clarifying when the Harrises moved from one place to another. Wayne Harris talked about being a military family, and that Eric was often the new kid in school. “Did that seem to cause any problems for him?” someone asked.

“No, not that we were aware of,” Wayne said. “I mean, he seemed to adjust very well.” (…)

Thomas said. “It was, I think during parts of it, very emotional. I mean, they were very distraught. I think both the Harrises expressed dismay at how this… how their son could have been involved in this. I would describe them as agonized. Physically, they appeared to really be in agony over all this.”

Wayne Harris groaned whenever events at Columbine were mentioned. “It was just like complete disbelief,” Thomas said.“Katherine Harris, Thomas believes, cried at one point. “Obviously, in conflict about, I think, some mixed feelings,” he said. “I mean, she obviously loved her son a great deal but obviously was pretty much aware of what he’d done but very conflicted over, ‘How could this be?’ I mean, ‘How could he have done these things?’”

Placed next to Wayne’s initial “flush him” remark, this meeting is important context. It shows that once the immediate shock subsided, both parents spoke about Eric with familiarity, affection, and grief, bringing photos, recounting his childhood, and trying to convey that he had been an ordinary boy within their family. At the same time, they were not minimizing the crime or pretending it hadn’t happened. What comes through instead is conflict. Love for their son existing alongside horror at what he had done, and an ongoing struggle to reconcile those two realities.

This is not the behavior of parents who were indifferent, uncaring, or eager to erase their child. It reads as two people trying, imperfectly, painfully, to understand how the son they loved became capable of something they themselves could not comprehend.

Shortly after that initial moment, so often reduced to a single line about “flushing” Eric, there are other, quieter indicators of how Wayne Harris was processing what had happened. These details rarely make it into public discussion, but they matter precisely because they are unguarded.

The morning after the massacre, before any sustained public scrutiny had properly begun, Wayne Harris made a phone call that had nothing to do with statements, lawyers, or damage control.

”On the morning after the massacre, Wayne Harris phoned the family dentist. Eric had an appointment June 30. He needed to cancel it.

Only later would Harris crumble in devastation.

“That feeling inside where you feel dead, too,” explained Derek Holliday, 20, a close friend of Kevin Harris who has visited the family several times since the shooting. “Pain, just pain.” ” – Los Angeles times 1999

Canceling an appointment more than a month away is a small act, but it reflects an immediate confrontation with permanence. It’s the practical recognition that there is no longer a future date to plan for. This kind of grief doesn’t announce itself. It shows up in routine tasks that suddenly become unbearable.

Placed next to Armistead’s account, this moment complicates the narrative that Wayne Harris reacted with dismissal or detachment. Shock, anger, devastation, and love are not mutually exclusive in the immediate aftermath of severe trauma.

April 22 1999

”From the family of Eric Harris

“We want to express our heartfelt sympathy to the families of all the victims and to all the community for this senseless tragedy. Please say prayers [for] everyone touched by these terrible events. The Harris family is devastated by the deaths of the Columbine High students and is mourning the death of their youngest son, Eric.” – LA times

2000

Nearly a year after Columbine, Wayne and Kathy Harris released their second public statement they would ever make regarding Eric, in relation to the anniversary of the shooting. By this point, the initial chaos had passed, but the reality of what had happened and the permanence of it had settled in. This statement was issued in the lead up to the one year anniversary, at a time when public attention and media scrutiny briefly surged again.

“We continue to be profoundly saddened by the suffering of so many that has resulted from the acts of our son. We loved our son dearly, and search our souls daily for some glimmer of a reason why he would have done such a horrible thing. What he did was unforgivable and beyond our capacity to understand. The passage of time has yet to lessen the pain.

We are thankful for those who have kept us in their thoughts and prayers.

Wayne and Kathy Harris.”

What stands out to me is the duality in this statement. There is no attempt to excuse or soften Eric’s actions, “unforgivable” is a deliberate and heavy word, but there is also no denial of love. “We loved our son dearly” is stated plainly, without qualifiers or defensiveness. They acknowledge the suffering caused by Eric first, before speaking about their own grief, and they describe an ongoing, unresolved search for understanding rather than closure.

The line “The passage of time has yet to lessen the pain” is also worth noting. Nearly a year later, their grief is described as unresolved and raw. In that context, delays, avoidance, or reliance on intermediaries for handling Eric’s remains do not read as indifference to me, but as part of a prolonged state of emotional paralysis.

I’ve highlighted these elements because they contradict the narrative that Wayne and Kathy Harris disowned their son or emotionally detached from him after his death. If anything, this reads as two parents trapped between grief, shame, love, and moral horror, still unable to reconcile how all of those truths can exist at once.

2001

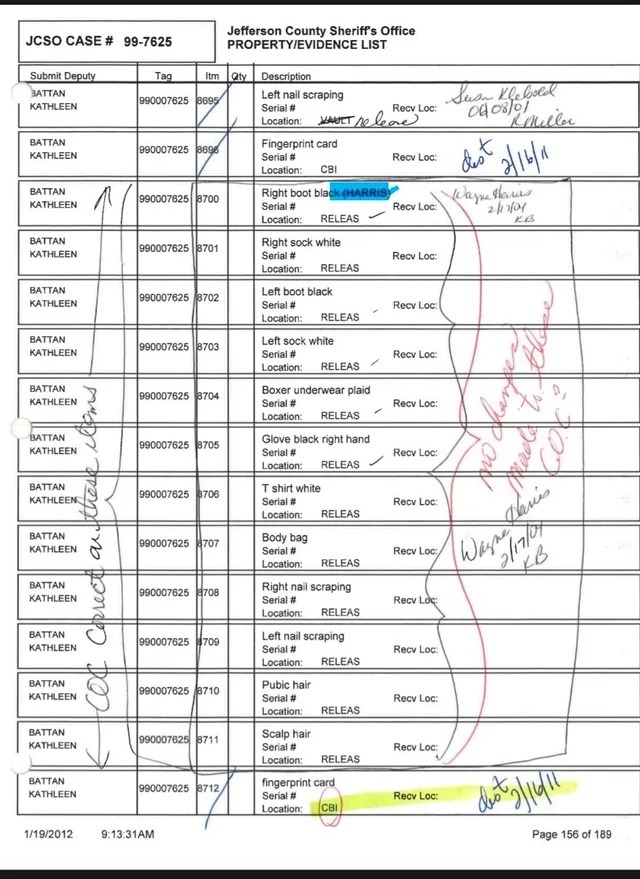

In 2001, Wayne Harris retrieved several items of autopsy related evidence connected to Eric, as documented in the Battan files. This is one of the few confirmed instances where the family directly took custody of materials tied to Eric after his death.

This is what was returned to the Harrises:

Items

Right boot black

Right sock white

Left boot black

Left sock white

Boxer underwear plaid

Glove black right hand

T shirt white

Body bag

Right nail scraping

Left nail scraping

Pubic hair

Scalp hair

Among other items listed elsewhere including:

his wallet with content

a leather case

a match striker

Some school books/Papers

Hand written notes

1996/1997/1998 yearbooks

Magnets

Cds

posters

photos

Doom Books

Eric’s class schedule/report cards

Clothes

If the family truly did not care about their son, there would have been no reason to claim any of these items. Unclaimed evidence could have been destroyed through routine procedures. Choosing to take custody, particularly of these items, suggests something other than indifference.

It’s also worth noting that this included biological materials, DNA samples such as blood, hair, and nail scrapings, as well as the body bag itself. These are not items stand out to me. If concern about items falling into the wrong hands existed, it would more plausibly have involved private collectors rather than the press. Even under that assumption, however, the logic doesn’t fully hold. If the primary concern had been preventing misuse, Eric’s ashes would eventually have been retrieved as well regardless of how they would have felt about him.

Choosing instead to retrieve these items points to an intent to take responsibility for Eric’s physical remains. I don’t believe this was motivated by fear of exposure or collection. I believe it reflects care for their son, complicated by grief and the emotional limits of what they were able to face at the time.

2007

In 2007, Wayne and Kathy Harris agreed to meet privately with Tom and Linda Mauser. This meeting is often referenced because it is one of the rare moments where the Harrises spoke directly to victims’ parents, albeit outside the public eye. Because Wayne and Kathy declined to comment publicly on the meeting afterward, we only have the Mausers’ account of what was said. That matters. What we’re reading here is filtered through grief, interpretation, and the impossible emotional position of everyone involved.

A common takeaway people latch onto is the idea that the Harrises “accepted” Eric as a psychopath. I don’t fully agree with how that conclusion is often framed. That characterization reflects the Mausers’ perception of what they heard, but it’s also worth asking what language is even available to parents in that situation. When sitting across from people whose child was murdered by your son, what can you say that acknowledges the harm without sounding defensive, minimizing, or self-exculpatory?

“Wayne did most of the talking. He is a retired Air Force major and sounded like one, careful and precise in his language. Wayne was mystified by his son. Wayne and Kathy accepted that Eric was a psychopath. Where that came from, they didn’t know. But he fooled them, utterly. He’d also fooled a slew of professionals. Wayne and Kathy clearly felt misled by the psychologist they sent him to.

The doctor had brushed off Eric’s trademark duster as “only a coat.” He saw Eric’s problems as rather routine. At least that’s the impression he gave Wayne and Kathy.They shared that perception with the Mausers. Other than the van break-in, Eric had never been in serious trouble, they said. Eric rarely seemed angry, his parents said. There was one odd incident where he slammed his fist into a brick wall and scraped his knuckles. That was startling, but kids do weird things. It seemed like an aberration, not a pattern to be worried about.

Wayne and Kathy knew Eric had a Web site, but that didn’t seem odd. They never went online to look at it. Kathy shared lots of loving stories about Eric. She described supervising him closely, particularly with the community-service work he was assigned in the juvenile diversion program. Eric got behind and nearly missed a deadline, until he charmed a supervisor into signing him in for hours he hadn’t actually worked. His parents found out and made him go back, put the time in.

(…)Wayne defended Kathy as “a good mother.” Kathy worked, but said she was always “available” for Eric. She insisted on meals together, as a family. Shortly before the murders, Kathy had picked out Eric’s graduation cake: yellow, with chocolate frosting.(…)Senior year, Kathy was distressed about Eric’s lack of college or career plans.(…)

Kathy thought he might end up at a community college, so maybe that explained things. Linda found Eric’s mother sincere and convincing. And haunted. Wayne and Kathy seemed involved in Eric’s life, at least as much as an average parent.

(…)Eric didn’t seem interested in joining a lot of clubs, or pursuing a wide circle of friends. But he dated and all that seemed normal enough. They had him in professional counseling, and taking antidepressants.The situation seemed under control.(…)

But the topic of child abuse came up. No, they had never beaten Eric, the Harrises said, or been cruel to him.(…)Kathy cried several times and repeated how sorry she was this all happened. She turned to Linda at one point and confessed how scared she had been to come.(…)The couple told the Mausers they never planned to talk to the media; they didn’t think they could endure it.(…)”

Even here, seven years later, the Harrises still spoke about Eric with familiarity, detail, and affection. Kathy shared ordinary, loving memories. Wayne defended her as a mother. They described involvement, supervision, concern about his future, and regret over missed warning signs. At the same time, they framed Eric in clinical, distancing language, psychopath, fooled us, we didn’t know, language that creates moral and emotional distance, especially when speaking to victims’ parents.

To me, this doesn’t read as parents who stopped caring about their son. It reads as parents trying to hold two incompatible truths at once. That they loved Eric, and that acknowledging that love publicly, or even privately, could feel unbearable, inappropriate, or harmful to others. Their continued silence, then, does not signal a lack of care, but an attempt to protect themselves emotionally while not centering their grief over the grief of others.

That final point is especially important. When Wayne and Kathy told the Mausers that they never planned to speak to the media because they didn’t think they could endure it, it provides direct context for their long-term silence. Their absence from public discourse has often been interpreted as coldness, avoidance, or indifference. This account suggests something far simpler and more human. That they did not believe they were emotionally capable of surviving public scrutiny, judgment, and repeated exposure of their grief.

Seen alongside everything else described in this meeting, the visible distress, Kathy’s fear about attending at all, the care with which Wayne chose his words, their silence appears less like a statement and more like self preservation. It aligns with a consistent pattern in how they handled the aftermath. Minimizing public presence, limiting exposure, and keeping their relationship to Eric private.

That context matters when assessing later choices as well. Silence does not equal lack of care. In this case, it appears to be part of how Wayne and Kathy Harris managed an ongoing, unresolved grief that never fully left them.

2008

By 2008, nearly a decade after Columbine, the Harrises were still largely absent from public view. One of the few documented moments where Wayne appears indirectly is through author Wally Lamb, whose novel The Hour I First Believed engages heavily with the psychological, moral, and communal aftermath of a school shooting. Its based of Columbine. While the book is fiction, it is deeply concerned with grief, survivor responsibility, and the long shadow violence casts over families and communities, making Lamb a meaningful figure for Wayne to approach, rather than a journalist or commentator.

Lamb has spoken about how apprehensive he was traveling to Denver on his book tour, unsure how his work would be received in a city still closely tied to the trauma he was writing around. It was during this visit that an unexpected encounter occurred, one that Lamb himself clearly never forgot.

”Still, he was nervous before going to Denver on his book tour. “I didn’t know what the reaction would be,” he says. During his stay, he expressed to a local paper his interest in the older brothers of Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris. “I always wonder what happens when a brother does this,” he says.

At a book signing, one of several he did in the city, a man waited in the long line to meet him, and when it was his turn, he said to Mr. Lamb, “Do you think this would be a good book for Eric’s brother, Kevin, to read?”

Mr. Lamb was stunned. “All of a sudden it dawned on me that it was Eric Harris’s father,” Mr. Lamb says gently.

“He was like a walking embodiment of sadness and grief,” he continues. “I was at a loss for words. I put my hands out,” he explains, extending his arms with palms turned up to demonstrate. “And he took mine in his, and we held each other’s hands for 30 seconds.”

Mr. Lamb sobs, unexpectedly, at the memory. His voice cracks, and he wipes away tears.

“It was painful and very powerful,” he says after a moment’s pause, his voice catching again.

“I don’t have any answers for you,” he recalls saying.

“I don’t have any answers, either,” Mr. Harris responded.

“How is Kevin?” Mr. Lamb inquired.

“Not so good,” came the reply. The elder Harris child had joined the army to get away from the tragedy and the notoriety, the father explained. He is currently in Afghanistan.

“I gave him my e-mail address,” Mr. Lamb says now. “And I told him, ‘If you want to talk about things, or if there are things you want me to know after you have read the book, please contact me.’ It was so brave of him to come to this [book signing] He is still searching to try and sort this all out.”

The author composes himself again. “It really hits home about the responsibility. I have been trying to process the whole thing ever since.”

What’s striking here is not just Wayne Harris’s grief, but the form it takes. He doesn’t seek absolution, explanation, or public sympathy. He asks whether a book might help his surviving son. He stands in line like anyone else. He admits he has no answers. This is not the behavior of someone detached, dismissive, or eager to erase the past.

This encounter also reinforces something that appears again and again in the record. Wayne Harris gravitated toward private, human exchanges rather than public platforms. He did not go to the media. He did not speak in interviews. He approached an author whose work grappled with moral aftermath rather than blame, and did so quietly, without drawing attention to himself.

Taken alongside everything else this moment fits the same pattern. Silence was not indifference. It was restraint and care. And grief, for Wayne Harris at least, appears to have remained unresolved long after the public had begun to move on.

2010

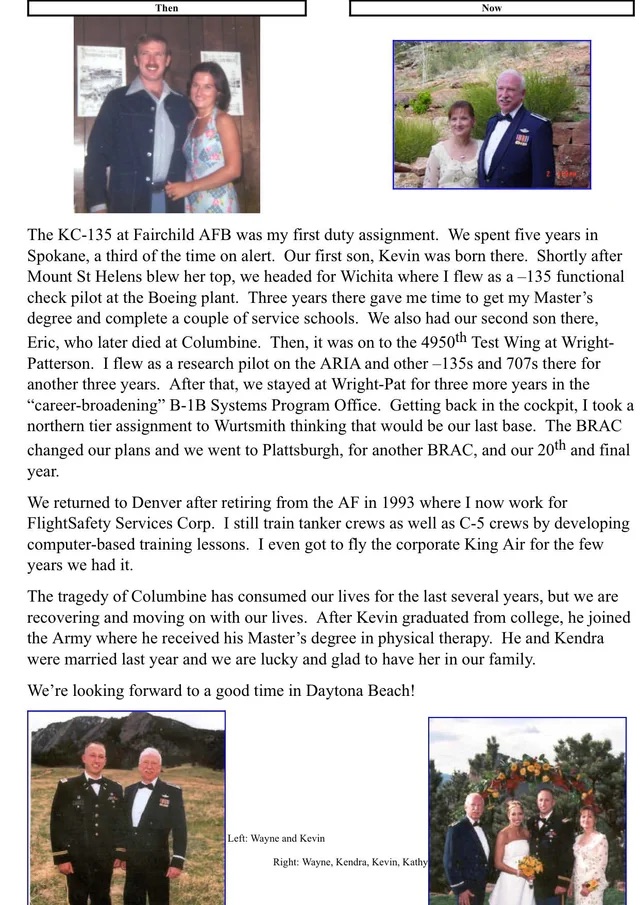

Lastly, there is Wayne Harris’s own writing. In 2010, over a decade after Columbine, Wayne referenced Eric on his personal website while discussing his career, his family, and his life after the tragedy. This wasn’t a media statement, an interview, or something issued under pressure, it was a self authored space, where every word was optional.

“We also had our second son there, Eric who later died at columbine (…) the tragedy of columbine has consumed our lives for the last several years, but we are recovering and moving on with our lives.”

That does not read as disownment. Eric is named as his son, his death is acknowledged directly, and the impact of Columbine is described as something that consumed their lives for years. At the same time, Wayne allows himself language about recovery and continuation not because the loss ceased to matter, but because living indefinitely inside that moment was not survivable.

This matters, because by 2010 Wayne had nothing to gain from maintaining a particular public image. If the intent had been to distance himself from Eric entirely, there would have been easier ways to do so, by omission, vague phrasing, or silence. Instead, Eric remains part of the family narrative, even if spoken about carefully and briefly.

Taken together with everything before it, the early shock, the later reflections, the meetings, the retrieved effects, the long silence, this forms a consistent pattern. Eric was not erased. He was carried quietly, privately, and with limits.

All of this is relevant to where I believe Eric’s ashes currently are. But to explain that reasoning properly, it’s necessary to first look at Timothy McVeigh because the handling of McVeigh’s remains provides important context.

Who was Timothy McVeigh? Tap to read.

Timothy McVeigh was an American domestic terrorist responsible for the Oklahoma City bombing. On April 19, 1995, he detonated a truck bomb outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. McVeigh was arrested shortly after the bombing, convicted on federal charges in 1997, and sentenced to death.

McVeigh himself disclosed to reporters at The Buffalo News in New York that he had considered having his ashes spread at the memorial site.

“That would be too vengeful, too raw, cold. It’s not in me. I don’t want to create a draw for people who hate me, or for people who love me,” McVeigh said.

He was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001, at the federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana.

Where are the ashes now?

When you step back and look at the full record, a pattern emerges, one that is often lost when individual moments are taken out of context or reduced to a single quote. Over the years, Wayne and Kathy Harris have spoken rarely, cautiously, and always with restraint. When they have spoken, they have acknowledged Eric as their son, expressed love for him, and struggled openly with the reality of what he did. They have never denied the harm, never minimized the crime, and never attempted to place themselves at the center of public sympathy. What they chose instead was silence.

That silence has frequently been misread. Because the Klebolds spoke publicly and engaged with the media, they are often perceived as more remorseful, more loving, or more “human.” The Harrises, by contrast, are framed as cold, uncaring, or ashamed of Eric. But the evidence doesn’t actually support that distinction. It supports something else entirely. Two families responding differently to the same unimaginable trauma.

The Harrises’ approach, private meetings, limited statements, refusal to engage with the media, reads not as indifference, but as self-protection. They were explicit about this as early as the Mauser meeting, where they stated they never planned to talk to the media because they didn’t think they could endure it. Everything that followed aligns with that boundary.

That context matters when considering what happened to Eric’s remains.

In Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism released in 2023

It is stated that Eric’s ashes were kept on the same shelf as Timothy McVeigh’s until McVeigh’s remains were scattered in the mountains around 2001.

According to that account, Eric’s ashes were stored in an investigative locker under Ellis Armistead’s control until Nigh retrieved McVeigh’s.

As already discussed, Armistead was the investigator entrusted with Eric’s remains, who worked with the family well and later handled McVeigh’s remains as well.

It’s also worth emphasizing that the last documented reference to Eric Harris’ ashes places them in storage in 2001, around the time Timothy McVeigh’s remains were scattered. After that point, the record goes quiet.

When Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism was released in 2023, it reignited speculation around Eric Harris’ ashes in a way that detached the account from its actual timeframe. The reference to Eric’s ashes being stored alongside McVeigh’s dates to around 2001, yet it only entered broader public discussion more than twenty years later. In that gap, assumptions filled the silence, with some imagining his ashes abandoned indefinitely in an evidence locker. That leap ignores both the chronology and the documented reality of the Harris family’s state in the immediate aftermath. Two years may seem long in hindsight, but in the context of profound trauma, legal constraints, and emotional paralysis, time moves differently. Notably, that period coincides with when the family slowly began reclaiming Eric’s personal effects and autopsy materials, steps that suggest gradual capacity rather than neglect.

Afterwards there are no subsequent mentions of Eric’s ashes being transferred, scattered, or destroyed. That silence coincides with the period in which we see repeated, documented instances of the Harris family continuing to grieve Eric privately, through statements, personal interactions, and later, Wayne’s own writing.

As mentioned before, when viewed alongside the broader timeline, that overlap matters. The absence of further documentation after 2001 does not suggest abandonment, it aligns with a pattern of private handling. From that point forward, the Harrises consistently chose non public avenues for processing their grief. Taken together, it is reasonable to conclude that Eric’s remains were no longer in institutional custody, but with his family or their legal representative.

What we do have is documentation showing that Eric’s body was released to Aspen Funeral Home, with no services held, per power of attorney:

“Eric Harris Body Released to Aspen Funeral Home 1350 Simms (303) 232- 0985, No services for Harris per Power of Atty to Private Investigator. Bill Black works at Aspen (303) 232- 0985.”

Beyond that point, the paper trail ends.

But that silence does not exist in a vacuum. When you place it alongside everything else, the retrieval of Eric’s personal effects and biological material, including DNA and the body bag. The later statements acknowledging love and unresolved grief. The private meetings where Eric was spoken about with detail and familiarity. Wayne’s quiet encounter with Wally Lamb. and finally Wayne’s own written acknowledgment of Eric on his website in 2010. A consistent picture forms.

The Harrises did not erase their son. They carried him privately.

For me, the fact that they retrieved such emotionally difficult autopsy materials is strong circumstantial evidence that they also retrieved Eric’s ashes eventually, either personally or through their attorney. Even if one were to argue that concern about items falling into the wrong hands played any role, and I don’t believe it was the primary motivation, the same logic would apply even more strongly to his ashes. If they were worried about misuse or exploitation, leaving them unclaimed indefinitely would make little sense.

My view is that Eric’s ashes were not scattered with McVeigh as many assume. More likely, they were either kept by the family, scattered somewhere private known only to them, or possibly buried in an unmarked plot. And even in the unlikely scenario that they were not immediately retrieved, it is reasonable to expect that Armistead or the family’s attorney would have retained them, allowing the family to decide when, or if, they were emotionally able to act.

What we can say with certainty is this. There is no confirmation that Eric Harris’ ashes were ever scattered, and no public record of where they are today. Given the totality of the evidence, everything points to his parents taking responsibility for them in the same quiet, restrained way they handled everything else.

The public narrative has often been unfair, shaped by assumptions about what grief is supposed to look like and how it should be performed. Wayne and Kathy Harris lived their grief privately. In cases like this, the families are victims too, even when their child is the one who caused the harm. That reality does not mean they cut him off, erased him, or stopped loving him. In fact all evidence we do have, point to the fact that they always continued to love him, keep his memory alive privately while respecting others grief and working with their own.

Clear timeline

20th April 1999

Eric commits the crime and diesCirca 20th April 1999

Private investigator Armistead

‘Just flush him’21th April 1999

Wayne cancels Erics dentist appointment

Soon after

Meeting with the police, explaining Erics life, pictures, emotional

Some time in 1999 Eric gets cremated and the ashes gets picked up by their private investigator

April 19th 2000

Only public statement by the Harrises‘We loved our son deeply’

2001

Wayne picks up Erics belonging and autopsy evidence2001

Mcveigh gets executed, cremated and put in the same shelf as Eric. Soon after he gets picked up and scattered.2007

The Harrises meet with The Mausers

Remorseful, careful, loving memories of Eric2008

Wayne goes to the book signing of Wally Lamb.

Broken, looking for answers2010

Wayne writes about Eric on his website

Columbine deeply affected them, loss of Eric2023

The book with the detail about Eric ashes and Mcveigh gets published.

Speculation runs wild

Leave a comment